In a new study published in the Journal of Neuroscience, researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Human Development and the Max Planck Institute of Psychiatry in Munich suggested that people who can frequently have lucid dreams—that is, dreaming with awareness they are dreaming—actually have measurably bigger brain structures in the prefrontal cortex than those who do not.

The Max Planck researchers also found that lucid dreamers score higher on self-reflection and thought-monitoring tests when awake, suggesting that lucid dreamers are more “lucid” during the day too.

It’s a fascinating study, and I’m making up a big batch of popcorn while I watch the fallout on social media between lucid dreamers and non-lucid dreamers, who often vie for being “better” or “more evolved” dreamers. Good clean fun.

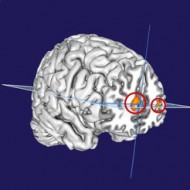

Anyhow, researchers found that subjects who say they have frequent lucid dreams have larger brain structures in the anterior prefrontal cortex. This area of the brain has been previously associated with many aspects of what we call higher ordered thought or executive function thinking.

Metacognition: How we think about thinking

The fancy word for this type of high ordered thinking is meta-cognition, which I’ll loosely define as layered thought processes that can perceive other self-arising forms of thought, such as noticing your present emotional state, or thinking about your own self-awareness, and make adjustments based on this information.

Metacognition is something that is usually attributed only to humans. It’s not just high brow armchair-sittin’ and navel-gazin’, but is actually the foundation of creative thought, classical reason, emotional intelligence and novel invention.

You know how early human species used the same boring stone tool set for like a million years, and then more advanced humans came along with bigger brains and started popping off new tools left and right, and also working with fire, using language, burying their dead and making beads and nuclear weapons?

You know how early human species used the same boring stone tool set for like a million years, and then more advanced humans came along with bigger brains and started popping off new tools left and right, and also working with fire, using language, burying their dead and making beads and nuclear weapons?

Metacognition, ya’ll: it’s what paid for the party.

Honestly, though, we don’t do it as much as we say we do (sort of like sex). That’s why meditators meditate, and why lucid dreamers practice reality checks…. but I’m getting ahead of myself here.

The method of this recent Max Planck study was simple. They divided subjects by using a survey of how much they lucid dream. Once sorted, subjects then were given 11 minutes of two different metacognitive tests while being monitored in the fMRI — the 3D brain-scanner that shows brain activity in real time.

Both groups showed increased activity in the frontopolar cortex (The Brodmann Areas 9 and 10) during the tests (previously associated with higher order thought and self monitoring) but the high lucidity group had higher activity, more increased oxygen flow and greater increases in general in these regions.

The conclusion here is that metacognition in waking life and lucid dreaming can be said to share at least some neural characteristics.

Metacognition in perspective

Cognitive psychologist Tracey Kahan and lucid dream researcher Stephen LaBerge suggested over a decade ago that the very definition of lucid dreaming is itself a very specific form of meta-cognition. When lucid, we not only know we are dreaming, but we know that we know. This meta-knowing leads to the ability to make choices, remember intentions, and focus our attention selectively in the moment as the dream continues to unfold.

Kahan, LaBerge and other cognitive scientists have been mapping these connections for years, developing sophisticated phenomenological analyses of lucidity, volitional consciousness and metacognition. Tracey Kahan has gone on to create a complex quantitative study of metacognition (for dreams and waking life) called MACE, and Ursula Voss has also created a consciousness analysis in the same vein called the LUCiD scale.

When cognitive psychologists publish press releases, pop science blogs generally don’t cover it (because there’s no pretty pics of brains all lit up), and that’s too bad as a fine toothed comb sifting through the qualities of interior experience is absolutely necessary if we really want more understanding of this topic.

What IFLScience And Scientific American missed

Unfortunately, many of the pop science media sources that reported on this study insinuated (or flat out stated) this is the first neural support linking lucid dreaming and metacognition.

Actually, Max Planck researchers have had quite a few previous studies on this topic (which I covered back in 2012), as have other research groups that clearly associate lucid dreaming with higher activity in the prefrontal cortex (compared to non-lucid REM dreams). For example, check out this, this and of course I would be remiss not to nod to this.

What really makes this study interesting is it is beginning to close the loop: it is the first to focus specifically on metacognition in waking life and in dreams and also investigate the neural footprint of metacognition in self-declared lucid dreamers and those who are not.

Also, in the context of contemporary dream research, this study is giving the continuity theory of dreaming a new level of significance—a neuroscientific seal of approval—that suggests that the patterns of thought we engage in during the day can be mirrored in our dreams…and perhaps vice versa.

Can everyone expand their brains with lucid dreaming?

I am excited that the researchers at Max Planck plan to next study the ability to learn lucid dreaming, and see if learning how to lucid dream also increases waking metacognition and these associated brain structures.

Of course, we already know that lucid dreaming is learnable… this is what Stephen LaBerge and his colleagues at the Lucidity Institute have painstakingly been demonstrating for several decades. Several groups of studies by other researchers have shown lucid dreaming can be learned rather quickly for some.

And anecdotally, of course, many people (myself included) have found that increased activities related to thought-monitoring (such as meditation, journalling intentions, and performing reality checks) can increase dream recall and lucidity in dreams.

But no one has specifically looked at how learning lucid dreaming can change the brain. I’m hopeful, and reminded of the studies about how the practice of meditation can transform the brain in a number of weeks (and, uh, apparently our DNA too).

Can learning to lucid dreaming also deeply effect us (and future generations) in this way? Stay tuned.

First image: CC meta body.

only look forward to receiving more about learning to lucid dream .

I find the competitiveness of lucid dreamers distressing and distracting from the value of dreams as a whole. The point is to value dreams as a rich resource regardless of the size of your brain. Let’s change the focus away from egocentrism.

I agree! although I’ve seen the competitiveness with both groups. Those with a Jungian outlook can be especially derisive towards lucid dreamers. In the end, it’s how you grow from your dreams that matters most.

Hi Ryan, great piece. I’m very curious about the Jungian take on lucid dreaming, and the possible sources of aforementioned derision … in case you can point me in the right direction? Thanks!

Hi Albert, Jung never mentioned lucid dreaming–or at least, not as it is defined today. I actually don’t know any sources off-hand: in print, Jungians ignore lucid dreaming. Rather, I have heard the debate in the hallways of academia and especially at academic conferences. For a wonderful and mature integration of Jungian thought and lucid dreaming, see Mary Ziemer’s work here: http://www.luciddreamalchemy.com/