Although the scientific community did not recognize lucid dreaming until 1978, the history of this unique dreaming experience reaches back thousands of years, and potentially into the Paleolithic Era. However, the first verifiable documentation of lucid dreaming originated in the East thousands of years ago.

Hinduism and Buddhism

The first known textual description of lucid dreaming dates to before 1000 BCE from the Upanishads, the Hindu oral tradition of spiritual lessons, philosophy and proverbs. The Vigyan Bhairav Tantra is another ancient Hindu tract that describes how best to direct consciousness within the dream and vision states of sleep. In the early centuries, Indian influence spread to the mountainous region of Tibet, where the animistic tradition of Bonpo maintains that lucid dreaming has been used in their meditations for over 12000 years.

The textual legacy that has survived the cultural fusion of this shamanic practice with Buddhism is the Tibetan Book of the Dead, conservatively dated to the 8th century. The partial translation of this esoteric track in 1935 by Walter Y. Evans-Wentz was the first time a Western audience, primarily historians and occultists, learned of these ancient practices. These ancient dream practices later influenced dream scholars in the 20th century, especially with the Humanistic and Transpersonal schools of American psychology.

The textual legacy that has survived the cultural fusion of this shamanic practice with Buddhism is the Tibetan Book of the Dead, conservatively dated to the 8th century. The partial translation of this esoteric track in 1935 by Walter Y. Evans-Wentz was the first time a Western audience, primarily historians and occultists, learned of these ancient practices. These ancient dream practices later influenced dream scholars in the 20th century, especially with the Humanistic and Transpersonal schools of American psychology.

Classic Greece and Islam

In the West, the concept of lucid dreams is almost as old as Western letters itself. In general, dreams had a privileged position in the foundations of Greek philosophy; Socrates, Plato and Aristotle all addressed their inquiries into the nature of reality to our nightly journeys. Lucid dreams were first clearly described by Aristotle (350BC), in his treatise On Dreams. Aristotle writes, “when one is asleep, there is something in consciousness which tells us that what presents itself is but a dream.”

A few centuries later, in 415AD, the first lucid dream report was recorded, from one of St Augustine’s patients.

Lucid dreaming may have played an integral part of the history of Islam. Mohammed’s Laylat al-Miraj is an account of a nighttime vision that provided him with spiritual initiation. The 12th century Spanish Sufi Ib El-Arabi suggested that controlling thought in dreams is an essential ability for aspiring mystics.

Three hundred years later, Sufi mystic Shamsoddin Lahiji recorded an inspiring night vision of the heavens that also may have been a lucid dream experience. Due to cultural and historical differences between the distinction of visions and dreams it is impossible to know for sure if this account, as well as Mohammed”s, occurred during sleep or vision states, but they are certainly lucid.

The dark ages of lucidity

Despite these strong classic beginnings, the study of lucid dreaming became stifled by the dominant religious atmosphere after the rise of Imperial Rome. Judea-Christian culture came to hold a suspicion about dreams, as theologians opined that that some dreams had access to higher truths, but others were false.

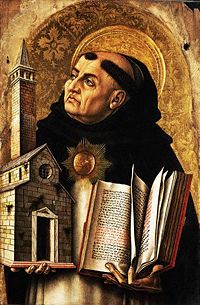

In the Middle Ages, Thomas Acquinas reinforced this opinion, suggesting that some dreams come from demons. After this warning on high, the Christian West’s concern with dreams lay dormant for centuries, and lucid dreaming went underground.

In the Middle Ages, Thomas Acquinas reinforced this opinion, suggesting that some dreams come from demons. After this warning on high, the Christian West’s concern with dreams lay dormant for centuries, and lucid dreaming went underground.

This misconception of dreams is probably the single greatest reason why Western culture still ignores dreams and why many superstitions about dreams persist. In many Christian cultures today, for instance, lucid dreaming is still associated with satanism and witchcraft.

Lucid Dreams in the Enlightenment

In the seventeenth century, lucid dreams began to surface again, this time couched within the European culture of reason. Many dreamers shelved old superstitions and began to look inward again (or at least talk about such explorations openly). Pierre Gassendi and Thomas Reid are two Enlightenment era philosophers who discussed having waking-life levels of scrutiny and cognition within their dreams.

Interestingly, Rene Descartes, who is most famously regarded as being dismissive of subjective reality, actually wrote passionately about his lucid dreams in a private journal known today as the Olympica. Some dream researchers, such as Kelly Bulkeley and Harry Hunt, have suggested that Descartes” lucid dreams helped him frame his scientific method that was born from the statement “Cogito ergo sum.”

As cyber-philosopher Donald Challenger has joked, a more accurate statement from Descartes” early days may be “Somnio, ergo sum.” I dream, therefore I am. Descartes kept his dream investigations secret to his dying days, perhaps due to the intense social pressure of the Church as well as his scientific circle.

This is only a brief, sweeping history of the early days of lucid dreaming. For more depth, consult the resources below, particularly Laberge (1988). Lucid dreaming has been no doubt practiced in hundreds of more settings, but it is actually our dim Western view of dreams that enable the concept of “lucid” dreams in the first place.

In many other cultures, historic and contemporary, dreams are considered to be paths to knowledge, and dream incubation is common, so there is no need for the term “lucidity.” This is one of the ironic truths of lucid dreams; conceptually they exist primarily in relief of “ordinary dreams” which are dull, passive, and without import. In this way, lucid dreaming can be seen as a rediscovery of ancient practices as well as a recovery of our dreaming senses.

Continue the discussion with my article about lucid dreaming in the modern West.

References consulted:

Bulkeley. K. (1995). Spiritual dreaming. New York: Paulist Press.

Hunt, H. (1989). The multiplicity of dreams. New Haven: Yale Press.

LaBerge, S. (1988). Lucid dreaming in Western literature. Gackenbach, J. and LaBerge, S., eds. Conscious mind, sleeping brain. New York: Plenum Press, pp. 11-26.

Moss, R. (1996). Conscious dreaming: a spiritual path for everyday life. New York:

Three Rivers Press.

Shafton, A. (1995). Dream reader: contemporary approaches to the understanding of

dreams. Albany: SUNY press.

Shah, I. (1964). The Sufis. New York: Anchor Books.