“I had my knife. My intent was clear, and the stone with its ancient glyphs lurked in the distance across the grassy, rugged moor.”

“I had my knife. My intent was clear, and the stone with its ancient glyphs lurked in the distance across the grassy, rugged moor.”

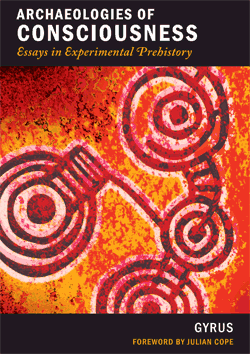

So begins the Introduction to Archaeologies of Consciousness by Gyrus. This one line captures the essence of this collection of essays: embodied research combined with literary grace and a dash of danger.

Most of the essays in this collection have been previously published in various esoteric magazines, but they have been freshly edited in this new volume. And frankly, these essays are more powerful together than on their own, because they reveal an intimate portrait of a scholar’s growth and maturation of thought.

Intimate: that is how I would sum up Gyrus’s independent research on the topic of experiential prehistory. The essays are unabashedly personal, exposing Gyrus’s biases and fascinations that he consciously projects onto the prehistoric monuments of England and Scotland that he has had personal contact with for decades. As he puts in it the Introduction, “Experiments with ritual, altered states, dreamwork and general larking about with consciousness have formed an integral part of my study of prehistory.”

Gyrus’s approach is part of an important revival in the Human Sciences, towards embodied knowledge and participatory research. By making his biases and theories transparent, he is providing a refreshingly honest approach towards his objects of inquiry. Indeed, as modern neuroscience has indicated, our perception of reality is largely governed by projection and interpretation. According to Antonio Damasio, even reason itself is an emotional process.

To put it bluntly, there is no objective reality. And this is especially true when dealing with such nebulous foci as prehistoric sacred sites. So by making his process transparent, Gyrus’s research is made all the more useful for others.

Through the essays in Archaeologies of Consciousness, Gyrus’s goal is to help his readers recover their own intuitive knowledge. It’s no secret that the default techno-rationalist worldview of Western culture has stripped us of our own senses, focused as it is on material production, visual stimulation as distraction, and a denial of the grief we feel from our separation from the natural world.

In other words, by spending time with ancient sacred sites, and in nature in general, we have an opportunity to remember who we are. Gyrus writes “city walls are the rigidification of human ego barriers writ large.” His ideas about prehistoric sites are therefore not just informed by the literature but also his extended personal experiences at these locations.

As such, Archaeologies of Consciousness succeed at cognitive archaeologist Paul Devereux’s call to balance empirical observations with subjective experiences in order to achieve a more holistic view of the phenomenon in question.

Or as Gyrus himself puts it, “I am my experience.”

This more holistic perspective is long overdue for both anthropology and archaeology. But of course, it has its dangers. Indeed, doing subjective research can be a much more difficult process than the demands of classic empiricism. I can speak of this personally as my work as a field archaeologist as well as a dream phenomenologist. Subjective analysis can be prone to self-deception, aggrandizement of character, as well as wildly inaccurate pet theories that do not take empirical methods into account.

In my view, Gyrus balances his more fanciful imaginative work well with the available data on the prehistoric megalithic and rock art sites of the British Isles. This is no easy task and is hopefully a sign of times to come for the discipline at large.

However, my favorite essays in this collection are the ones that are more focused. The first essay of the collection “Devil and the Goddess” is full of insights but loses some traction for me as the subject matter swims all over the place, from modern death metal bands, to the ancient neolithic site of Avebury, to UFO theories. (On a related note, I love the narrative analysis of UFO reports as having a suspicious “space age clinical myth-structure.” Great line, and also parsimonious with my views of the relation of these reports to lucid dreams, sleep paralysis and so-called OBE experiences.) Yet, the thesis of the essay cannot be found for some fifteen pages, and only then does the essay take shape. While I appreciate imaginative endeavors such as this, as a reader I need more initial guidance.

The later essays show a more honed structure, revealing Gyrus’s maturation as a writer and researcher. The three middle essays each discuss issues of prehistoric rock art interpretation, and particular locales where the theories are “brought home.” This is participatory research at its best: focused, embodied, and productive of new insights that complement traditional archaeological methods.

In these core essays, Gyrus plunges headlong into the current debates about the role of shamanism and altered states of consciousness in the production of rock art and the construction of prehistoric sites. This hot topic has been reviled by many in the archaeological community as faddish and merely a projection of “hippy-dippy” values based on suburban lost youth and a romantic view of the prehistoric past.

However, quantitative research by Jeremy Dronfield, valid ethnographic research by David Lewis-Williams, and empirical work by Brian Hayden all point to a shift in attitude in the anthropological community towards a probable correlation between altered states of consciousness and some Paleolithic and Neolithic art around the world. Those who are against this consideration refuse to debate the data and rather argue based on their entrenched worldview, much like the substantial data gathered in anomalous psychology and dream studies.

Gyrus is aware of the seduction of self-deception as he asks, “Can we really grapple with this sort of subjectivity when envisioning the distant past?” By asking this question he has revealed the central dilemma of archaeology as a field of inquiry: Is this a Science or a Human Science? Most archaeologists are content to count glass beads and stick to the modest truth claims that scientific materialism offers archaeology: that people lived here, quarried there, and threw their trash down in that ditch.

But the spirit of archaeology is of course asking larger questions, which we can only call questions of meaning: What do these curious abstract images on the rocks signify? Why did they bury their dead in this way? And ultimately, what did people believe? These questions, which comprise the heart and inspiration of the discipline, squarely place archaeology in the realm of the Human Sciences.

In a sense, as Gyrus notes, this work is dangerous because it loosens the boundaries of archaeology, “boundaries that have been diligently erected in archaeology’s long struggle to gain the status of being a “science.”” Indeed, there is a constant but unstated threat for archaeologists that they better behave, or the Academy is going to take their white coats away. They”ve only had those coats for some forty years, after all.

Of course, archaeology is more than a science, and that is its strength. As a inter-disciplinary field, it offers one of the more integral approaches to research in the contemporary West. Optimistically, I believe that archaeology is ready for a truly holistic approach, one that values the empirical, as well as the subjective and the more ephemeral intersubjective realms that Gyrus treads. Archaeologies of Consciousness is an example of how authentic and personal exploration can lead to new insights – not only of the researcher’s own worldview, but of the world and our place in it.

Now, if you want to know what Gyrus does with his knife, you”re going to have get your own copy.