Do you know who first coined the phrase “lucid dreaming”? Most sources point to Frederik van Eeden and his 1914 paper presented to the Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research in London.

But actually, nearly 50 years before that, a French man by the name of Marquis d’Hervey de Saint-Denys used the term “rêve lucide,” and discussed how he was developing the ability of “being often aware of my true situation while sleeping… and therefore keeping sufficient control of my ideas to guide their development in whatever direction suited me.”

But actually, nearly 50 years before that, a French man by the name of Marquis d’Hervey de Saint-Denys used the term “rêve lucide,” and discussed how he was developing the ability of “being often aware of my true situation while sleeping… and therefore keeping sufficient control of my ideas to guide their development in whatever direction suited me.”

Sigmund Freud never got a hold of Saint-Denys’ work: what would have happened to psychotherapy if he had?1

However, many other dream enthusiasts did read Saint-Denys, including Van Eeden. Saint-Denys’ interest in “dream control” really sparked the rationalist movement in dream studies. He used his lucid dreams as an experimental tool, testing theories and making observations about how objects and dream figures behaved.

This is a fascinating point of departure in the historical development of dream research: the dream is seen not just as an experience one has had, but a methodology.

As Harry Hunt points out, Saint-Denys’ theory of dream formation is eerily prescient of 20th century dream theories in neuropsychiatry, focusing primarily on memory processes, and specifically on the transformation of verbal thought into visual imagery. Freud didn’t take kindly to that, and saw Saint-Denys as a competitor against his own theories.

Saint-Denys’ dreams were beautiful and impactful too, and his rêves lucide might also be seen to have elements of what we call “big dreams” or “archetypal” dreams. Sometimes they read like Victorian vampire novels. For example,

“I dreamed I was transported to a sort of temple—dark, immense and silent. I was drawn by an irresistible curiosity towards an altar of ancient design which was the sole lighted object in this solitary and mysterious spot. An inexpressable emotion warned me that I was about to witness something unheard of….”2

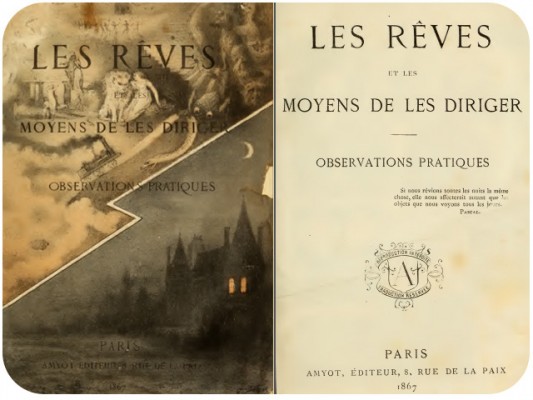

But get this: Saint-Denys’ work Les Rêves et les Moyens de les Diriger (which translates as Dreams and the Ways to Direct Them) has never been fully translated into English until a few years ago. (The quote used above from Saint-Deny’s dream is from an attempt made back in 1982, which resulted in a very incomplete translation, which sadly lost the spirit of the original text.)

You can now read an English translation of Dreams and the Ways to Direct Them on Kindle here.

References cited:

1 LaBerge, Stephen. 1985. Lucid Dreaming. New York: Tarcher.

2 Hunt, Harry. 1989. Multiplicity of Dreams. New Haven: Yale Press, p. 78.

First Image: Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog, by Caspar David Friedrich, 1818. Hamburg, Germany

In 1988/1991 Drs. Eli Meijer and myself publiced in Lucidity Letter/Lucidity an historical article on Saint-Denys. We had a.o. rediscovered the full original content of Saint-Denys’ work, and added with this publication the ‘lost’ Appendix, entitled ‘A dream after I took hachich’ in an English translation. You can read/download this article (website edition with additional data) at http://members.casema.nl/carolusdenblanken/Downloads/SDENYS.PDF

The original article circulates at the internet too at several sites.

thank you Drs. den Blanken! When I had access to the Lucidity Letter 10th anniversary addition at my university library, I kept it checked out in my name all the time. It’s a wonderful piece of scholarship.

Wonderful article about an important Kickstarter project for lucid dreamers.

I feel lucid dreamers will see that an experienced lucid dreamer, like Saint Denys in his book, reports and confirms many of the same insights and ideas of modern day lucid dreamers. This shows that the underlying psychological processes exist similarly for lucid dreamers across time and culture.

Hope others will support this effort, as I have!