Last month, G. Scott Sparrow, Ralph Carlson and I presented the initial findings for our retrospective study at the annual meeting for the International Association for the Study of Dreams in Virginia Beach, VA.

Despite the popular interest in galantamine, there is very little published research on its effects on dreams and lucid dreaming (knowing you are dreaming while in the dream).

The popular interest in galantamine for lucid dreaming began in the 1990s with Stanford University psychophysiologist Stephen LaBerge’s attempt to patent the substance as a dream enhancing substance (known technically as an oneirogen).

Although the patent failed, the word got out and thousands of people have since discovered for themselves the potent effects of galantamine on dreams, creating a very specialized nootropic subculture along the way that has popularized many other dream herbs and substances as well (for example, see Thomas Yuschak‘s book Advanced Lucid Dreaming, Scott Stride’s YouTube videos or any of the lucid dream forums such as Mortal Mist.)

You can read more about galantamine’s effect on the brain here, as well as my own experiences with the oneirogen. My own, and G. Scott Sparrow’s, personal experiences with galantamine dreams inspired this study, especially when we realized the lack of peer-reviewed research on the topic.

Our Aims and Methods

In our study, we investigated a range of effects that galantamine (a popular cholinesterase inhibitor) is anecdotally associated with in regards to lucid dreaming. Because the study is retrospective, we did not attempt to determine the effectiveness of galantamine for inducing lucid dreaming, but rather how lucid dreams preceded by the ingestion with galantamine compare with lucid dreams that were not under the influence of galantamine.

Participants filled out an online survey titled “Survey for Ascertaining the Subjective Differences Between Lucid Dreams Preceded by the Ingestion of Galantamine and Those Not Preceded by Galantamine.”

We received 19 completed surveys, all from individuals who have had previous experience with using galantamine specifically for inducing lucid dreams. In fact, the participants were all very experienced, and reported using galantamine on average of once a month.

The survey had 27 questions and assessed 14 characteristics of lucid dreams, including: vividness, bizarreness, fear, violence, out-of-body sensation, emotion, presence of companion/guide, perception of darkness, length, felt meaning or impact, and degree to which the dream figures seemed real or autonomous.

Findings

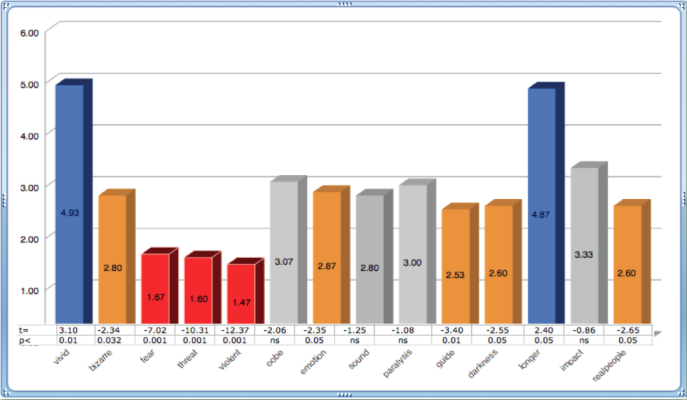

This bar graph (above) displays the variations from a hypothesized mean.

The blue bars represent significant positive differences (p<.05) in vividness and length of dream.

The orange bars show significant negative differences (p<.05) for dream bizarreness, emotionality, presence of guide, presence of darkness, and autonomous figures.

Interestingly, the red bars show strongly significant differences (p<.001) for presence of fear, threats, and violence.

Saliently, lucid dreams associated with galantamine were reported to have increased vividness and length less dream bizarreness and emotionality, and much less fear or violence.

Because this is a retrospective survey, we have to be careful with interpreting these initial results. Indeed, this is just the start: showcasing what dreamers who use galantamine for lucid dreaming report about their lucid dreams. As such, it can reflect the culture of galantamine use as much as anything else. There could be demand effects, and all kinds of other limitations, especially as the actual experiences were far removed from their remembering and reporting.

Still, a tentative interpretation from this data set is that galantamine’s reported benefits (reduced fear, increased length) may outweigh its potential unwanted effects (such as presence of sleep paralysis or terrifying dreams). This could be a significant finding for a potential clinical use of galantamine to induce lucid dreaming for the purpose of reprocessing and resolution of unresolved conflict and trauma.

Our next step is to compare the post-galantamine lucid dreams and non-galantamine dreams that were collected from each participant in this survey. We also aim to do more statistical work (analysis of variance) and finally, hope to conduct a longitudinal, double-blind study from which we might infer causality.

To download the full poster, click here.

First Image: Snowdrop by Brian Fuller, 2012 CC

I’m curious if anyone in the study mentioned the reason I’ve stopped using galantamine: it messes with my mood the next day. After using galantamine, I feel depressed and jittery the next day. It ended up not being worth it because of the low mood, although I will probably try it from time to time to see if it continues to have that effect on me.

Hi KMG! It was not mentioned because we did not ask about daytime mood. But I’m not surprised about this reaction. Supplements really do have a diverse collection of after-effects. Just like with whole herbs, there is a synergy between plant and human. In this light, sounds like galantamine might not be your ally.