This morning, Christmas Eve day, I noticed a holiday card on the coffee table. It was slightly crumpled and curled around the bottom as if it has been discarded for a while. I opened the card and gasped – it was signed by my grandmother, who died four years ago this month. The card must have been mixed in with one of the ornament boxes and then, when my spouse had cleaned up, the card remained.

This unexpected and bittersweet joy – this Christmas ghost – warms me. It’s as if my grandma showed up in her full-sized sedan that was always spotlessly clean, flashing her playful smile and holding her signature stuffing in a white and blue Pyrex dish.

Dang, I miss my grandma.

Here’s the truth: one of the often overlooked aspects of this holiday is nostalgia, and the somber accounting of who is here, and who is not. There is a mourning aspect to the holiday; the Christmas blues are always here, cast like a shadow and given stark dimensionality by the holiday lights and cheer.

Christmas is all about ghosts, and always has been of course.

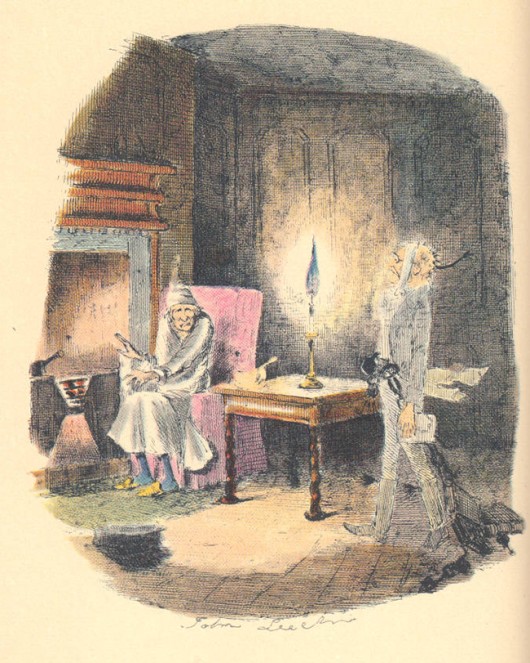

But no one has reinforced this modern ghost-centered holiday more than Charles Dickens.

And Dickens, as it turns, out was frequent experiencer of vivid dreams, dreams intruding into waking life, and sleep-induced spiritual encounters.

As dream scholar Gregory Rosa suggests, Dickens was a master lucid dreamer. (If you’re not yet, follow Rosa’s newsletter Dream Treasures — it’s wild, and his recent piece inspired this here article).

Rosa writes, “Ebenezer has no less than three intense lucid dreams in that novella, preceded first by a humdinger of a harbinger of a hallucinatory visitation, before he trip balls through the past, present, and future over the course of one long transformative night.”1

Let me back up to say, there’s been a lot of literary analysis over the years that has focused on the dream-infused worlds of Dickens. We’ve been diagnosing Scrooge every time we reread A Christmas Carol, or more likely, rewatch the movies (We’ll be sticking to Bill Murray’s version this year).

Dickens was known to be an insomniac, and a man of waking visions who famously dealt with his sleeplessness by taking to walking the streets at night, which gave him a close and personal view of how the poor and unhoused citizens of London were suffering.2

Many have suggested that Dickens’ insomnia led to hypnagogic hallucinations, which typically emerge while falling asleep or while waking up. However, sometimes hypnagogic visions would intrude into waking life, much like the vision of Marley’s face on the door knocker.

I’ve personally experienced this before, when I was working in Alaska one summer in a salmon cannery. We were working 90- 100 hours a week, and sleeping when we could, in tents on a high bluff facing the Kenai inlet. I was incredibly sleep deprived and the monotony of the work led to several waking hallucinations, which I learned I could induce at will. I remember focusing on the idea of Lucky Charms while endless cans of fish passed by my station; I was delighted when –as clear as day – an imprint of stars, moons and four leafed clovers superimposed itself on my waking life surroundings. They were organized in a tight repetitive grid like you might see on a sheet of blotter paper, and they shimmered and danced. That was a clue I really needed to get some rest.

Yet I don’t think Dickens was inspired by this sort of hypnagogia – characterized by fleeting and seemingly disconnected images, noises and smells—when writing the scenes of the Christmas Carol in which Scrooge is visited by four ghosts. (Yes, four, Marley counts).

Rather, I suspect Dickens was drawing from his experience of hypnagogia entrained by sleep paralysis, which manifests frighteningly real encounters with supernatural agents who loom over the bed, and sometimes, take the dreamer on an otherworldly journey. Historically and cross-culturally, this type of dream vision is often interpreted in line with a culturally-specific supernatural assault tradition.3

One of the calling cards of these experiences is they feel like waking life – the dreamer swears “this is not a dream” because, unlike most dreams, the dreamer tends to still have their waking-style thinking online. We can look to the text for support of this notion:

“You don’t believe in me,” observed the Ghost [of Marley].

“I don’t.” said Scrooge.

“What evidence would you have of my reality, beyond that of your senses?”

“I don’t know,” said Scrooge.

“Why do you doubt your senses?”

“Because,” said Scrooge, “a little thing affects them. A slight disorder of the stomach makes them cheats. You may be an undigested bit of beef, a blot of mustard, a crumb of cheese, a fragment of an underdone potato. There’s more of gravy than of grave about you, whatever you are!”4

This wonderful description also points towards a common 19th century explanation for nightmares – that they are caused by indigestion. Except in the 19th century, nightmares did not refer to “bad dreams that wake you up” (as we talk about nightmares in the 20th century) but sleep paralysis night-mares – ie supernatural assault visions in which the dreamer feels awake and aware and is struck paralyzed by an evil force that can go on to “ride” or harass the dreamer.

This wonderful description also points towards a common 19th century explanation for nightmares – that they are caused by indigestion. Except in the 19th century, nightmares did not refer to “bad dreams that wake you up” (as we talk about nightmares in the 20th century) but sleep paralysis night-mares – ie supernatural assault visions in which the dreamer feels awake and aware and is struck paralyzed by an evil force that can go on to “ride” or harass the dreamer.

This gastronomical theory dates back all the way to Galen, and was still quite in vogue in Dicken’s time. The theory basically goes that the over-full stomach presses on the diaphragm and/or somehow impedes circulation to the heart and lungs which triggers the mind into an emotional panic.5

By the way, the indigestion theory for night-mares actually still has wings: in 2006, Takenori Ikeda and colleagues investigated heart health after subjects ate a huge meal. Subsequent ECG abnormalities were indeed noted, suggesting that a large meal before sleep could lead to ventricular fibrillation in folks who have poor heart health – or an unknown deadly heart defect like Brugada syndrome, which is the likely cause of death in Hmong refugees who suffered terrifying sleep paralysis and then died in their sleep.6

And speaking of horrors leading to art – this is the case that inspired Wes Craven to write and direct Nightmare on Elm Street.

Anyhow, Dickens surely knew of sleep paralysis nightmares; he actually described the symptoms of the condition some 40 years before the affliction was medically recognized. In Oliver Twist, Dickens suggests,

“There is a kind of sleep that steals upon us sometimes, which, while it holds the body prisoner, does not free the mind from a sense of things about it, and enable it to ramble at its pleasure. So far as an overpowering heaviness, a prostration of strength, and an utter inability to control our thoughts or power of motion, can be called sleep, this is it; and yet we have consciousness of all that is going on about us, and, if we dream at such a time, words which are really spoken, or sounds which really exist at the moment, accommodate themselves with surprising readiness to our visions, until reality and imagination become so strangely blended that it is afterwards almost a matter of impossibility to separate the two …”7

Let’s zoom in to the specific aspects of Scrooge’s experience which are so often mentioned in regards to intruder visions and sleep paralysis-linked supernatural assault: the sound of footsteps, the dragging of chains, and finally the supernatural night visitors looming over the bed followed by lucid and guided visionary experiences, similar to Emmanuel Swedenborg’s tour of the cosmos a century before, as I’ve discussed in my book Sleep Paralysis.8

Taking into account all these strands of evidence, I’d say Scrooge’s ghostly encounters are a fairly accurate depiction of a sleep paralysis-entrained hypnagogia or REM intrusion into waking life, followed by powerfully emotional and existentially gripping lucid dreams.

On the lucid dreaming front, Gregory Rosa points out:

“Notice how Dickens, through his fictional lucid dream persona Ebenezer, confronts the nightmarish memories of his early life, the same way any modern dreamworker will tell you to confront your nightmares to transform and banish them from your psyche. Indeed, all throughout the tale, Dickens-Ebenezer expertly interprets his dreams in real lucid dreamtime, and he’s pretty darn Jungian spot-on — which is impressive, given that Dickens wrote the story a full 50 years before Freud’s “The Interpretation of Dreams” was published, when William James was still in cotton nappies.”9

Regardless of the validity of A Christmas Carol connection to sleep paralysis and supernatural assault—as theories come and go—the story sticks with us, sort of like a fragment of an underdone potato.

A good ghost story brings lucidity: it stirs our fears, and with it, heightens our vigilance and provides us a chance to notice how we respond to the world – and even change our ways.

As I sit with a little sadness and melancholy on this particular Christmas eve (the sun is setting as I type these words, we are entering the liminal zone), I am resolving to make space for these undigested feelings tonight, to notice who is here, and who is gone; to notice what I can be grateful for; and to bear witness and alleviate whenever possible the suffering of others.

I’ll leave the last word on Dickens to dream researcher Kelly Bulkeley, who suggests, “Dickens wants us to know that in dreams, especially dreams at this time of year, anything is possible….”10

Love you Grandma. Your stuffing really couldn’t be beat.

Notes

1 Rosa, G. (2023). Ebenezer Scrooge, Master Lucid Dreamer. Dream Treasures. Substack: Published December 23, 2023.

2 Gomes and Nardi (2021). Charles Dickens’ hypnagogia, dreams, and creativity. Frontiers of Psychology: 12: 700882.

3 Adler, S. (2010). Sleep paralysis: Night-mares, nocebos and the mind-body connection. New Brunswick: Rutger.

4 Dickens, C. A Christmas Carol.

5 Jones, E. (1951). On the nightmare. New York: Liveright.

6 As quoted in Adler, p. 126

7 Cosnett, J.E. (1992). Charles Dickens: Observer of sleep and its disorders. Sleep. 15(3):264-267.

8 Hurd, R. (2011/2020). Sleep paralysis: A guide to hypnagogic visions and visitors of the night. San Mateo: Enlightened Hyena Press.

9 Rosa.

10 Bulkeley, K. (2019). The wise nightmares of a Christmas Carol. Dreaming in the digital Age: Psychology Today.