Sigmund Freud is considered the father of dream science, even though most of his dream theory is largely discredited today. But from the get-go Freud assumed that dreaming was an expression of the mind-brain system, a premise still widely accepted by scientists, psychologists and philosophers today. Still, in popular culture, we still hear the question asked, “Do dreams have meaning? or are they random bits of brain trash?”

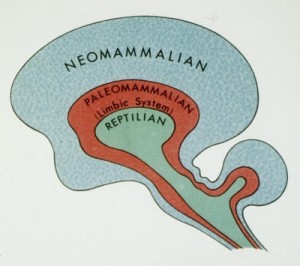

So let’s take a look at the neurological and cognitive evidence, focusing on the brain layer by layer. Many parts of the brain contribute to the experience of dreaming: from the lower brain and upwards to the middle and higher brain structures. Nihilists may gnash their teeth, but judging by the theories coming out of neuroscience today, it appears that meaning is built into the fabric of dreaming itself.

The Lower Brain Structures REM sleep

Evolutionarily speaking, the brain stem is the most ancient part of the human brain, shared by all vertebrates. In 1977, Allan Hobson and Robert McCarley discovered that electro-chemical pulses from the brain stem create the architecture for REM sleep. Not all dreams occur in REM sleep of course, but it is this stage of sleep that provides the relatively active mind state where many of our remembered dreams occur. These brain stem pulses create the substructure of the dreaming experience, including how long the REM period lasts.

Evolutionarily speaking, the brain stem is the most ancient part of the human brain, shared by all vertebrates. In 1977, Allan Hobson and Robert McCarley discovered that electro-chemical pulses from the brain stem create the architecture for REM sleep. Not all dreams occur in REM sleep of course, but it is this stage of sleep that provides the relatively active mind state where many of our remembered dreams occur. These brain stem pulses create the substructure of the dreaming experience, including how long the REM period lasts.

The idea that these brain stem pulses are essentially randomly generated has been misinterpreted by many a journalist to mean that the content of dreams is also randomly generated or “meaningless.” Rather, this hypothesis suggests that the function of dreaming is primarily physiological. Psychologists don’t dispute this. And as Hobson himself has clarified, he does think that dreams have psychological meaning—in fact Hobson has kept his own dream journal for decades.

What about the idea that dreams are the defragging of the brain — the process of deleting information? This theory comes to us from Francis Crick and Graeme Mitchison in 1982, known as the “reverse learning theory of dreams.” While it conveniently mirrors computer science, the evidence for defragging as the function of REM is rather poor, and most scientists do not support it today.

The Middle Brain Integrates Emotions

When dreaming sleep begins, the middle brain becomes an electro-chemical fireworks display of activity. In fact, the middle brain is so active in REM sleep that Hobson (1999) has appended his theory of brain generation to suggest that it may be just as responsible for the structure of dreams as the lower brain. This part of the brain is shared by all mammals. Also known as the limbic system, it regulates emotional responses and cravings. During dreaming, the middle brain is more active than it is in waking life, so you could say that emotional intelligence is the guiding structure here.

One part of the middle brain is especially active: the amygdala, a walnut-sized lump that philosopher Rene Descartes, and later Emmanuel Swedenborg, once thought was the seat of the soul. Today, we call the amygdala is the seat of emotion, and especially fear, due to its role in maintaining fight or flight responses.

But why so emotional? Dream researcher Rosalind Cartwright argues that we are replaying old memories and updating them with information from recent experiences. This is emotional logic: it’s not about cause and effect, but emotional correspondences. Cartwright’s laboratory research suggests that most dreams are negative in emotion, the most common ones being fear, anxiety, anger and confusion.

This idea is mirrored in the evolutionary theory of dreaming, which supposes that dreams rehearse possible threats. Threats from the past are important data in this sense, showcasing how a dream can both be about the past and future simultaneously.

The Higher Brain Takes a Nap

So, when we’re we are in dialogue with a talking bear, how come we usually don’t realize that we’re in a dream? Neuroscientist Allen Braun (and company) published a provocative finding in 2002 using new evidence from brain imagery scans. They discovered that, during dreaming sleep, the higher brain is essentially offline. The higher brain is the newest part of the brain –the cortex—and humans have the most grey matter, as well as the most infolded grey matter, in this layer than all the other mammals. Braun argues that the prefrontal cortex—which generates language, logic, and critical thinking–is taking an electro-chemical siesta while we argue with that talking bear.For whatever reason, we largely accept the bizarre landscape around us.

Working memory may be out to lunch, but something is oddly familiar when we are in the dream itself. Perhaps, as depth psychologist James Hillman argues, there’s a part of ourselves that belongs in the dreamworld, and is quite comfortable with the rules of the realm.

Working memory may be out to lunch, but something is oddly familiar when we are in the dream itself. Perhaps, as depth psychologist James Hillman argues, there’s a part of ourselves that belongs in the dreamworld, and is quite comfortable with the rules of the realm.

Something similar happens in other highly creative states. For example, a recent fMRI study (Limb & Braun, 2008) showed reduced activation in the prefrontal cortex when expert jazz musicians were spontaneously jamming compared with when they were playing memorized pieces. From this perspective, dreaming sounds like a flow state as defined by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, not a deficiency in cognition.

Keep in mind, some critical thinking still occurs in dreams, as we actually co-create dreaming outcomes when we “work around” the weird plot changes and bizarre visual imagery that the other parts of the brain throws our way. Indeed, cognitive psychologist Tracey Kahan has amassed plenty of quantifiable evidence that we have meta-cognition in dreams. Metacognition used to be thought of as the pinnacle of waking thinking, and dreams were assumed to be completely devoid of it. Kahan’s data shows that we still think about our feelings, ponder decisions, and wonder about what’s going on around us in the dreaming narrative.

The extreme of this trend in metacognition, of course, is lucid dreaming, which is when the dreamer knows “this is a dream.” Scientifically validated by Stanford psychophysiologist Stephen Laberge, lucid dreaming is marked by conscious choices, active thought, and logical reasoning in the dream. This claim was recently strengthened by researcher Ursula Voss in 2009, who along with her colleagues from Neurological Laboratory in Frankfurt, Germany, published strong evidence that the brain has heightened activity in the frontal and frontolateral areas during these “self-aware” dreams.

But where is the meaning? You decide, literally.

As cognitive psychologist Bill Domhoff has quantitative shown, the content of our dreams largely matches our interests, worries, and preoccupations from waking life. Domhoff’s evidence supports the continuity hypothesis for dreaming, one of the most widely supported modern theories of how dream content is formed, experienced in the moment, and interpreted upon awakening.

In my world, reviewing theories about how the brain creates and interprets the dreaming experience does not reduce dreaming to “only” a biological event. Rather, a holistic approach to dreaming must integrate the material, the psychological and the transpersonal to reflect the depth of our experience.

Today the question is not do dreams have meaning but rather emerges as:

what do you find meaningful?

References

Allan Hobson and R. McCarley, The Brain as a Dream State Generator: an Activation-Synthesis Hypothesis,” American Journal of Psychiatry 134 (1977), 1335-1348.

Psychology Today: Dreaming up a good mood

Voss, U., Holzmann, R., Tuin., Hobson, J.A. (2009). Lucid dreaming: a state of consciousness with features of both waking and non-lucid dreaming. Sleep, 2009 Sep 1;32(9):1191-200.

Balkin, Braun, Wesensten, Jeffries, Varga, Baldwin, Belensky, Herscovitch, 2002. The process of awakening. Brain, 125, 2308-2319

Kahan, Tracey and Stephen LaBerge. Dreaming and waking: Similarities and differences revisited. Conscious and Cognition, 2010

Limb, C. J., & Braun, A. R. (2008). Neural substrates of spontaneous musical performance: An fMRI study of jazz improvisation. PLoS One, 3(2), e1679.

First Image credit: Brain coral by bsmith4518

I went to bed last night with my iPad playing music next to me. I must have turned during the night because when I woke up, my Christmas playlist was opened and run, run, Rudolph was playing. My dream, if you can believe it, was tied into Christmas. It was about this: my it was like 7 pm and my dad was talking to my mom. He came in my room and said me and my sister had to go witth him to get the new version of Microsoft word because the old one broke. Then I went downstairs and realized that the living room was cleaned, and the chair was moved from the corner where the tree goes. We then went to buy our Christmas tree and came home to decorate it. I am kind of scared and fascinated by this strange coexistence.

hey Billy, my guess is that the music influenced your dream. this is pretty common: sounds, temperature, smells and other stimuli have been shown to be incorporated into dreams in many studies. still, the dream itself isn’t necessarily random, as it plays out a story that’s meaningful to you. I would say the dream points to your excitement about “clearing the way” for something special. Here’s a projection: if it were my dream, a new version of the “word” on Christmas day sounds like a good message from a Christian perspective. what else does “word” mean to you?

AWESOME Ryan, perfect integration and updated information. THANK YOU VERY MUCH!

Thanks for this. I like the phrase “brain trash” and feel like all the brain trash that I do become conscious of informs me from day to day. But I can’t help asking what is meant by “meaning”?

thanks Martin!

and Caitlyn – glad you asked 🙂 I’ve been using meaning in the general sense here as “personal significance.” But there’s really two ideas that can be teased apart:

1. human experiences that serve as signifier for other experiences, memories, and concepts.

2. conscious experiences having an internal structure.

meaningless in the first sense = unimportant or not significant; meaningless in the second = random, unstructured, completely chaotic.

Thanks Ryan, great read!

Another great article, Ryan!

(I’ve posted this dream on another article, I think it was how to get rid of nightmares or something) but I don’t see the significance of a nightmare about zombies. I go to bed with the same sounds, smells, and temperature every night and I have this dream at least once a week now. Is a zombie apocalypse coming?

zombies are a cultural symbol, and while I don’t know what it means to you personally, collectively zombies signify the “walking dead.” in other words, the feeling of being not quite alive, of being dead to life’s adventures, or being in a behavioral rut. zombies eat the brains of the living… they turn others into the undead too. apathy and boredom and the status quo is a catching disease!