The neuroscience of dreaming is a relatively new enterprise but has quickly become the major paradigm of experimental dream research today. J. Allan Hobson, Professor of Psychiatry Emeritus at Harvard University, is the undisputed celebrity of this scientific outlook, and the author of several popular books on the topic. Hobson, in his 30 years of tireless work, is also perhaps the greatest provocateur in the field of dream studies, stirring up old philosophical conflicts such as the value of objective science over experience, and mechanism over meaning.

But what Hobson is really known for is sticking it to Freudian theory. In his break-out 1977 paper, Hobson and co-author McCarley declared victory over Freud (and the entire psychoanalytic community) by reporting their discovery that dreams in the REM state form by grace of neurochemical changes in the brain. As Kelly Bulkeley notes (1994), Hobson presented his work as a polemic against Freud, whose influence he accused of preventing scientific progress in the study of dreams. His central beef with Freudian theory is the notion that dreams are full of hidden messages by design. On the other hand, Hobson agrees with Jungian dream theory that dreams reveal more than they conceal, and can be quite transparent in significance.

The Biochemistry of Dreaming

Hobson argues that dreams are clumsy narratives stitched together by the forebrain to make sense of the activation of biochemical changes and erratic electric pulses originating in the brainstem. This is Hobson’s theory of dream formation in a nutshell, which he has updated many times over the last 30 years, and is still referred to as the activation-synthesis hypothesis of dream formation.

The theory sheds light on several aspects of dreaming cognition. Most importantly, Hobson’s discovery of the role of neurotransmitters in dreaming has stimulated robust research into the biochemistry of consciousness and revolutionized the way that mental illness is conceptualized in psychiatry. REM dreaming is characterized by low serotonin levels and high acetylcholine levels, which may explain why dreams are so hard to remember: they are never encoded in short-term memory in the first place. When we wake up, serotonin floods the brain and our dream experiences from just a moment before are carried away by the tide.

Why are Dreams so Weird?

Hobson’s theory also offers a partial solution to why dreams are so wacky. In waking life, the brain performs reality checks and strings together logical stories to keep up with our thoughts, emotions and movements as we interact with the world. But in dreams, this ability is zapped when the serotonin valve is turned off, bringing about a state of consciousness ruled by strong emotions and uncanny sensations. It’s a chaotic place to be sentient, but the mind is so motivated to construct meaning that bizarre narratives are hastily thrown together so we can make order out of the mess. It’s a patch-job, at best, says Hobson.

Conflicts and New Solutions

One problem with Hobson’s original activation-synthesis model was that the theory presumes that all dreams occur in the REM state. However, two neuroscientists, James Foulkes and John Antrobus, have independently shown that long narrative dreams with bizarre elements can happen in non REM states too (see Rock 2004). Neuro-psychologist Mark Solms (1997) has also convincingly reframed the role of REM as an “alarm clock” for the mind to start dreaming, not as the prime creator. All of these researchers suggest that biochemical activation is not the sole genesis of a dream’s structure.

Hobson (1999) responded to criticism by modifying his position with some new brain imaging data that shows that the forebrain (specifically the limbic areas) are also highly activated in REM. The implication here is that emotions may be as big a factor in dream genesis/structure as brainstem activation. In other words, whenever someone suggests that “dreams are random nonsense,” you can helpfully remind them that view is 20 years out of date and even the anti-Freudians have since changed their tune.

Since then, Hobson has widened his research interests, and is now after the Holy Grail in scientific philosophy: the mind/body problem, also known as the hard problem: how does brain relate to mind and consciousness? Hobson’s contribution is the AIM model of consciousness. AIM reaches far beyond REM dreams, and predicts possible states of consciousness by mapping the states along three lines of inquiry (instead of just one as in activation-synthesis).

The AIM Model of Consciousness

1. Activation: how active is the brain, measurable in electrical activity?

2. Input source: is the generated imagery external, internal, or a combination?

3. Modulation: which neurochemical system is operating – the cholinergic (REM dreams and some altered states) or adrenergic (ordinary waking consciousness?

A fun example for AIM is lucid dreaming, which Hobson describes as a “hybrid state that features both waking and dreaming consciousness.” Recently, Hobson and his merry band found that while lucid dreaming is similar to ordinary dreams in modulation and input (ie both are cholinergic and made of internally-generated visual imagery rather than taking in information from the senses), lucid dreams have higher activation in the GAMMA (40hz) range in the frontal and frontolateral areas of the brain.

Mechanisms Don’t Trump Meaning

Many have made a straw man out of Hobson by misinterpreting his work as a defense against the meaningfulness of dreams. I have admittedly done so in the past before reading his primary works, no doubt influenced by all the rancor he stirred up in the psychoanalytic community. But in real life, Hobson is a dream enthusiast, and is reputed to have over 100 volumes of personal dream journals.

And more to the point, Hobson’s theory suggests that meaning and creativity are fundamental to the experience of dreaming, but that this meaning may not be present in the initial formation of dreams. Even as early as 1977, Hobson and McCarley suggested that dreams “are not without psychological meaning and function.” The significance of the dream narrative, in Hobson’s present view, comes only after the powerful neurochemical perimeters are set and interpreted by the higher-order parts of the brain that deal with language, logic and the mapping of emotions with remembered experiences.

However, despite his backpedaling, Hobson still believes dreaming consciousness is an epiphenomenon of biological causes.

Personally, I think that Hobson’s work cannot comment on issues of meaning, because his scientific paradigm has already bracketed out those subjective queries. And, besides, armed with an integral approach to science, learning about the material correlates to an extraordinary experience is not threatening to the value of the experience itself.

But if you believe in an immortal soul or a higher self that is unsullied by our gray matter, Hobson may disagree, after he offers to scan your brain.

For some great introductory reading by Hobson, check out:

Dreaming: An Introduction to the Science of Sleep by J. Allan Hobson

13 Dreams Freud Never Had:the New Mind Science by J. Allan Hobson

Additional References:

The Wilderness of Dreams by Kelly Bulkeley (1994)

The Mind at Night: the New Science of How and Why We Dream by Andrea Rock (2004)

Embodiment: Creative Imagination in Medicine, Art and Travel by Robert Bosnak (2007)

Allan Hobson and R. McCarley, The Brain as a Dream State Generator: an Activation-Synthesis Hypothesis,” American Journal of Psychiatry 134 (1977), 1335-1348.

Allan Hobson, “The new Neurospsychology of Sleep: implications for Psychoanalysis,” Neuro-psychoanalysis: An Interdisciplinary Journal for Psychoanalysis and the Neurosciences, 1(2): 159.

Mark Solms, The Neuropsychology of Dreams: a Clinico-anatomical study, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1997.

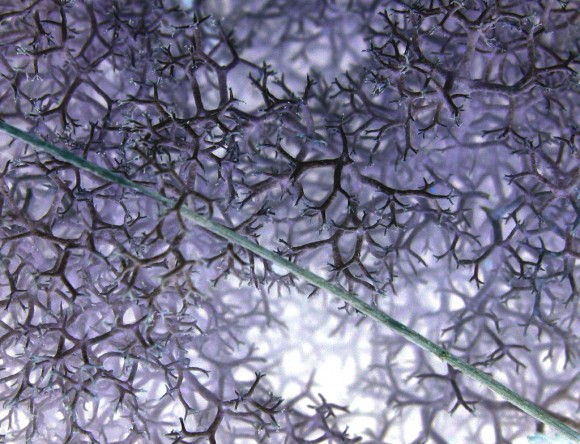

Introductory image (CC): Synapse by Mark Cummins

Hi Ryan,

I loved your piece which comments in an enlightened way on Hobson’s theory, and in particular his AIM methodology. My only question would be this: ‘Do all archetypes, cross -culturally’ have an integral scientific/materialistic explanation?’ Or ‘Are we really talking about Science’s attempt to analyze different and nested holarchies of Being?’ (Cf K Wilber)

I would be interested in your thoughts on the matter.

Warm regards, and Happy New Year from snowbound UK!

Hugh

Hello Ryan,

This is a terrific article. Like you (as I gather), I never had much use for Hobson’s apparent dismissal of meaning-centered theories. He has even admitted that his research arose out of a principled (and partly understandable) hatred of rudely overinterpretive psychoanalysts. Obviously, though, wanting something to be true (like that dreams’ meaning isn’t part of their function) doesn’t make it so. Yet I think you do a great, and very fair, job of summarizing Hobson’s evolving views. I now feel that I, too, should go back and read some of his primary works, rather than just blanketly dismiss him.

Eric

Hugh,

I have read Wilber with great interest – his integral theory can work with Hobson’s model, altho Hobson would disagree. From Hobson’s perspective, integral theory is not valid because it is not testable: it moves outside the bounds of scientific materialism. But from Wilber’s, the AIM maps only a quarter of the cosmos (the material correlates to consciousness).

Eric, thanks for your kind words and I’m glad to hear that you are rethinking the value of Hobson’s perspective. Whether or not AIM exposes the inherent meaningfulness of dreaming, there’s no debating that this perspective will continue to influence future generations of dream researchers and scientists.

Not sure that this should go here, but what the hell:

http://www.mpipks-dresden.mpg.de/~codybs09/POSTER_ABSTRACTS/dresler.html

The future answers to all our questions about dreaming will be much clearer thanks to this groundbreaking work by Dresler and colleagues. Unfortunately (for me at least), I came across this just as I was busy writing up a “proposed” neuropsychological model of lucid dreaming. Looks like the Germans beat me to it…ah well.

thanks for the link, Robert. German lucid dreaming research has always been top-notch. I can’t wait for someone to translate all of Paul Tholey’s work into English. what little I have seen has blown me away.

Hi Ryan,

I am writing a paper on this topic and have done a good bit of research on Freud, Jung and Hobson’s opinioin. I am most intrigued by Hobson’s approach and I understand that there is a chemical change happening when we dream, but what I’m not getting from Hobson’s ideas is why?? Why do the seratonin levels decrease and acetylcholine levels increase? What purpose does that serve? Is it merely an excerise tool for our brain? Or is there more too it that I am not understanding?

Your thoughts would be greatly appreciated!

Thanks,

Christina

Thanks Ryan for providing another nutshell perspective of important new work.

I am now going through a book which has 2 papers by Hobson. One of them discusses the biochemistry of the effects of prescription and recreational drugs on dreams and REM sleep, and contains aware warnings to potential users. I am not sure how much guidance is available to the public at large, in this area, especially with emphasis on what consumers, as opposed to specialists, should know.

Unlike with dream interpretation, sleeping is something everybody goes through. Larger segments of the population than are involved in the dream study movement must be in the market for sleep aids. This neuroscience related pharmacological industry must have some influence on the high volume of medical research that has now become a big, and it seems to me, different, branch of the “new” oneirology.

Thanks so much for all of this wonderful information on Hobson!!!!!!!!! I’m doing a presentation on him and I am very interested in what I’m continuing to learn about him.

???? Are there certain foods or drinks that help

you have prophetic dreams.

thanks and Take Care

sean

GReat Ryan, great! thanks

Hello Ryan,

As part of the honors program at my college, we read your article in conjunction with the first chapter of “Dreaming: A Very Short Introduction” by Hobson himself. I am a psychology major. Though I appreciate–and find interesting–the psychodynamic theory, it is simply too subjective for me. I land far on the cognitive side, and the Activation-synthesis model makes the most sense to me; dreams may open up to us processes that are occurring without our knowledge (the third level of cognition, as it were), but to deny the biological aspect of dream formation is shortsighted. If anything, the theory that the brain stitches together a storyline in its attempt to make sense of the information it processes even during a sleeping state pays homage to the vast power of our neurological network. Thank you for writing this article!

Ben

Hi Ben, thanks for adding to the discussion. Glad to hear you’re getting a chance to review different dream theories and decide for yourself what makes the most sense. Keep in mind that the Activation-synthesis model is still very controversial, even amongst neuroscientists. You may also be interested in the cognitive theories of Tracey Kahan, who is championing a meta-cognitive view of dream formation — this is the continuity theory of dreams. They don’t necessarily conflict — in fact, many dream theories can work together, because often dream researchers are only looking at one aspect of dreams at a time. So it’s always good to have multiple frames of reference — keeps the mind limber if nothing else! BTW – I’m curious which college you’re reading my work at! 🙂