What is the universal symbol for medicine?

What is the universal symbol for medicine?

Chances are, you thought of the caduceus – a staff with two snakes spiraling up, flanked with two outspread wings. Used today by thousands of doctors and medical associations, including the US Surgeon General, this image has a secret history that taps into an ancient mythological power.

But contrary to popular belief, the caduceus is not primarily a healing power. It wormed its way into our lives in a decidedly slippery way. In fact, the use of the caduceus as a modern medical symbol may actually be the result of a clerical error from the 19th century, in which the caduceus was mistaken for another, much older symbol of healing.

This medicinal bait and switch reveals the myths underpinning contemporary medicine, including where we came from, and how we may achieve balance moving forward.

Hermes Slips In

Sometime in the mid 1800s, the caduceus appeared for the first time as an insignia for hospital stewards in the US Army. Stewards were basically well-trained office managers for surgeons: they supervised nurses, prepared drugs, did the accounting, and organized meals. In 1871, the caduceus was further adopted by the US Marine Hospital Service, which protected and serviced merchant seaman and the growing international trade industry.

The use of the caduceus in these two roles –as business manager and as merchantile protector –makes some sense, as the caduceus is known in Greek mythology as the Staff of Hermes.

This god wears many hats and has a trickster nature. He is protector of sailors, shepherds, thieves, warriors and travelers: all ways of living that exist on the boundary-lands of human society. He also shepherds souls from that ultimate borderland, the realm of the living to the realm of the dead.

Most importantly, Hermes serves as the spirit of commerce and communication, dealing with exchange and negotiation.

In 1902, Hermes’ staff became the official symbol of the US Surgeon General, as well as the Medical Department for the US Army. Not all were happy about this choice, feeling the symbol had little to do with healing or medicine.

Hermes’ staff became the official symbol of the US Surgeon General, as well as the Medical Department for the US Army. Not all were happy about this choice, feeling the symbol had little to do with healing or medicine.

One astute editor wrote, “the rod represents power, the serpents stand for wisdom and the two wings imply diligence and activity, qualities which are undoubtedly possessed by our Medical officers.”1

But healing? Not so much… or so it seems at first glance.

Aesclepius: the Other Staff

So how did Hermes’ staff pick up the mantel of healing?

Many scholars argue that it was essentially a case of mistaken identity – the hospital stewards accidentally picked the caduceus rather than the traditional symbol of healing in Greek mythology: the Rod of Aesclepius.

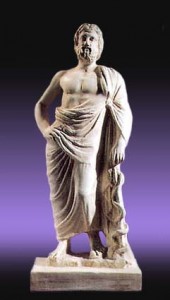

This rod is depicted with a single snake swirling around it. Almost no one today knows who Aesclepius is, and how he represents the beginnings of Western medicine, even though our medical professionals pledged allegiance to Aesclepius well into the 20th century when they recited the original Hippocratic Oath. (These days, the oaths to Greek gods have been scrubbed, although the original sentiment remains).

In Greek mythology, Aesclepius is known as the God of Healing. As a half-human son of Apollo, he teaches that healing is holistic. Vitality in life comes through exercise, proper diet, spiritual practice and mindful study.

During the Hellenistic era (the first three centuries of the Common Era), people flocked to thousands of dream incubation temples that were staffed by priest-physicians. In fact, dream temples made up the single most popular spiritual healing institution in the Mediterranean world, rivaling the early Christian Church.

These restful sanctuaries, set in beautiful settings, were designed to produce dreams that provided healing wisdom—and also instant cures—if we are to believe the boasts of ancient graffiti. Successful cures were honored with inscriptions on the walls of the sanctuaries, acting as advertisements as well.

The dream healers of ancient Greece were also surgeons and herbalists, teaching their young doctors the art of empirical observation coupled with an environment of safety and spiritual cleansing.

Key to the Aesclepian model of medicine is the patient’s responsibility for his or her own healing. Often, healing came from contact with the god Aesclespius — or one of his consorts — in a vision or dream that was incubated through a period of cleaning, meditation, prayer and sleep disruption, much like the contemporary vision quests of Native Americans.

Rather than limiting the endogenous healing response (often called the “placebo effect” today), Aesclepian rituals were designed to heighten, refine and direct one’s intention.

In the Aesclepian model, healing comes from within, especially when we are in balance with nature.

Hermes’ Pills and Other Tricks

Unfortunately, when modern medicine chose the God of Commerce over the God of Healing-–whether the choice was made consciously or not–our paradigm of healing changed as well. Hermes is an important figure to have around for accounting for lost souls when your patients are mostly dying soldiers, but not necessarily the best choice for many common soul ailments that metastasize as cancer, depression and other forms of chronic pain.

As others have noted before me, the commercialization of medicine and the rise of the pharmaceutical industry is a further parallel to Hermes-centric medicine. In this sense, medicine has flourished in the 20th century, although the healing process remains an enigma.

Still, there’s more to Hermes than cash money. He’s always got tricks up his sleeves.

We must not forget that within Hermes’ legacy is the alchemical tradition, which gave rise to the scientific side of medicine through chemistry and the scientific method. Hermetical traditions are esoteric – they are hidden from view by their very nature. It is in this context that we come back to the caduceus, which with its two intertwining snakes was seen as a symbol of divine balance and the refinement of base energies.

Andrew Weil, MD writes that the caduceus “embodies an esoteric truth that must be grasped to gain practical control over the shifting forces that determine health and illness.”2

Finding Balance in the 21st century

Interestingly, the balance of life and death is also a myth that comes with early myths of Aesclepius. In some tales, he carried two vials of Medusa’s blood: one that healed, and another that killed. Psychotherapist Edward Tick suggests that the ambivalence of Medusa’s blood highlights how important a secure container is for any exploration into healing.3

“That which heals can also kill.” This is central ethical statement of the Hippocratic Oath, because knowledge of healing carries tremendous power. When I think about the millions of people needlessly addicted to prescription drugs, and the millions of others who have given up all hope for a meaningful life because diagnosis = destiny, I wonder how we have allowed the healing profession to become so unbalanced.

Yet there has also been much positive growth in recent years, as more hospitals and wellness centers are incorporating holistic practices into treatment plans, and patients are given more psychological tools than ever before for directing visualizations and dreams, controlling anxiety, designing a healthy diet, and connecting with nature. All these skills are Aesclepian in nature, a return to the roots of Western medicine.

We need both the Aesclepian and the Hermetic side for the healing arts to make it in the 21st century, not just so we can beat back sickness, but so we can thrive.

What hangs in the balance is not the absence of sickness, but vitality. For Hermes, true healing comes with the transformation of poison into medicine, the rigor of chemistry and the material sciences, and the potential of radical transformation that comes when we court wildness, mystery, and bold exchange with the unknown.

For Aesclepius, the gifts include the holistic sanctuary, the ability for the patient to direct their own healing, as well as the ritual aspects that may allow for contact with the divine powers.

Seems to me, the tremendous growth of complementary and integrative medicine is the fruit of this union, which has just begin to ripen. In that light, I don’t care which symbol of medicine is currently in vogue… as long as healing is allowed to make its way.

References

1 Emerson, William K (1996). Encyclopedia of United States Army Insignia and Uniforms. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 181–182.

2 Weil, Andrew (2004). Health and Healing: The Philosophy of Integrative Medicine. Houghton Mifflin. p. 45–46.

3 Tick, Edward (2001). The Practice of Dream Healing. Quest Books. p. 25.

Thanks Ryan! This is just what the doctor (Aesclepius) ordered! Besides the good info and food for thought, just this morning I was playing with an idea that will draw on my MA which focused on the use of dreams in ancient Greece. Then the caduceus appeared in my inbox! The gods have spoken!

love it!

Thanks, Ryan. This is a great article. I envision a day, hopefully soon, when people understand that healing is a natural state of wholeness. Seems like people who call themselves “healers” miss this important fact … the healing comes about through understanding and alleviating symptoms can make it easier to heal but getting rid of symptoms is not in itself healing.

I’m glad that more people in the healing professions are learning to integrate spirit, mind, and body so that people can experience holistic healing.

Wonder how modern medicine might change if dream work were a part of the education for doctors and other people in the healing professions? (By the way, did you know that Ascllepius had three daughters: Meditrina (medicine), Hygeia (hygeine), and Panacea?

thanks Laurel. Your thought about healing itself as a state of wholeness is really thought provoking. Also reminded me of a Bob Dylan lyric “He who is not busy being borne, is busy dying.”

Well written and researched article Ryan, thanks for putting it out there.

Super interesting, I had no idea. Strangely enough, I just watched David Wilcock’s video about the pineal gland and its symbolism to ascension (transformation) shown consistently in history with 2 serpent heads.

In fact, in a google images search, older versions of the caduceus and even your illustration on the right show more of a pine cone shape than a sphere at the top of the staff.

It seems there must be some direct connection, but maybe not.

interesting about the pinecone connection. there may be something to it, dunno!

Important is the opinion of the divine nature of healing, but alas it is only opinion. Especially, when it is our own opinion.- It must be divine, since we ourselves are divine.-

Thanks for this, Ryan. I’m going to print it out and put it in the mailbox of all my co-facilitators at the cancer centers as a holiday gift.

🙂