Big Dreams are usually discussed in the popular media as dreams we remember for the rest of our lives. These could include emotionally intense dreams, powerful dream journeys, and visitation dreams.

Big Dreams are usually discussed in the popular media as dreams we remember for the rest of our lives. These could include emotionally intense dreams, powerful dream journeys, and visitation dreams.

However, the “dreams we remember for the rest of our life” are not the Big Dreams that contemporary dream researchers have demarked, but rather a watered down “catch-all” category that is based on the dreaming public’s perceived importance of particular dreams, rather than a set of features and characteristics unique to the experiences themselves.

Some researchers claim that Big Dreams come from different kinds of cognition than the typical REM dream. These typical dreams are the bread and butter of our dream life: chaotic stories, funny pairings of people from the past with situations of the present, anxiety dreams, etc. These “little” dreams are largely drawn from our personal past and tend to be loosely put together. We use narrative and story to help structure these experiences so we can talk about them.

Features of Archetypal Dreams

Big Dreams, also known as archetypal dreams, seem to be cut from a different cloth. Most importantly, they feel more real than real life, and a strong “felt meaning” is experienced in the moment. I think some visitation dreams definitely fit this description. But the other categories really set Big Dreams apart from ordinary dreams.

The most common elements are:

- abstract geometric patterns and kaleidoscopic mandalas,

- the experience of flying, floating or falling,

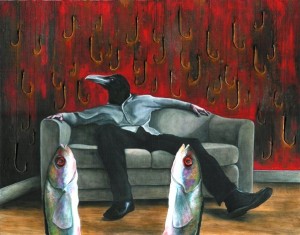

- encounters with mythological creatures and strange, intelligent animals

- feeling awe, fascination, fear and terror, and a sense of “Other”

Unlike ordinary dreams, these dreams are not easily picked at with standard dream interpretation procedures like psychoanalysis because very little personal history is encoded in these larger-than-life experiences. Archetypal dreams also have a consistency unmatched by ordinary dreams; in other words, their structure is cleanly focused, and the delivery to consciousness resembles waking visions of shamans and saints more than other nocturnal dreams.

Carl Jung and Big Dreams

The term “Big Dreams” came from Carl Jung, who seemed to dream in an archetypal way much of the time. But he made the distinction after visiting an East African tribe in Kenya, the Elgoni, in 1925. According to Jung, the Elgoni have a strong dreaming culture (80 years ago anyways – they have been successful at staying out of the eye of Sauron for many years since). They explained to Jung that there are little dreams and big dreams. For the Elgoni, big dreams were seen as collective dreams. The dreamer was dreaming for the community, for the landscape, and perhaps for all of the world.

This shamanic style of dreaming matched well with Jung’s own experience, and it gave him further insight into his theories of the collective unconscious (as a side note, later in life, Jung revised his earlier essays about the collective unconscious and moved away from theories dealing with “racial memory”, instead framing these shared experiences in a way that is more parsimonious with today’s evolutionary psychology: as bodily expressions transformed metaphorically into cognitive symbols that all humans share due to our common biological heritage.)

Archetypal Dreams and Mysticism

Consciousness researcher Harry Hunt has studied archetypal dream for 20 years, and has done more than anyone in helping re-frame these experiences in light of cognitive psychology as well as the world’s mystical traditions.

Consciousness researcher Harry Hunt has studied archetypal dream for 20 years, and has done more than anyone in helping re-frame these experiences in light of cognitive psychology as well as the world’s mystical traditions.

He notes in the Multiplicity of Dreams:

“The archetypal dreams of long-term meditators and other highly intuitive subjects, with their geometric (mandala) designs and forms of luminosity, convey an ineffable portent that when articulated sounds metaphysical and spiritual. These are more abstract levels of imagistic self-reference, based on structurally complex visual-kinesthetic synesthesias, with visual structures predominating. It is exceedingly difficult to see how such dreams could be based on the Freud/Foulkes model of translation from verbal-propositional thinking (p. 132).”

That’s a mouthful, and quoting Hunt is always dangerous because it makes me responsible for translating! Hunt is suggesting that archetypal dreams may have a different process than little dreams; his main point being that these expressions and experiences are not linguistically based and may not be formed from personal memory sources either.

The Origin of Big Dreams

So where do big dreams come from” And could archetypal dreams ultimately originate from the same cognitive soup as little dreams” John Antrobus, a retired professor of psychology and sleep research from City College of New York, thinks this is the case. His research into big dreams focuses on the emotional intensity of REM dreams that occur in the last part of the night, or early morning. From a recent New York Times article:

Core body temperature rises gradually from its nadir in the middle of the night during slow-wave sleep, the least active brain state. As morning nears, subcortical brain activity tied to the circadian cycle increases. When these cycles coincide in the last and longest REM phase, the study found, the mind produces its most dramatic dreams. Dreams during this active period are more likely to be highly memorable, vivid, and experiential, what Dr. Antrobus calls “superdreams.”

“The brain is waking up,” Dr. Antrobus said in an interview. “It starts waking up long before you are fully awake.”

Keep in mind that, for Antrobus, big dreams mean “memorable dreams,” and are not necessarily full of the archetypal elements that Jung and Hunt have described. Here, the emotional intensity of Antrobus’s “super-dreams” is the connecting thread. Perhaps the uncanny emotional level is one component that merges with the other, more complex, visual metaphors that comprise the unique characteristics of archetypal dreams.

This intense emotional element is also studied in the sociology of religion, in particular Rudolf Otto’s mysterium tremendum, which he described as the basic of mystical thought.

Archetypal Dreams & Ecopsychology

Returning to the shamanic Big Dreams of the Elgoni, perhaps these intense experiences with “Other” reveal communication with the larger-than-human community through our personal mythic and metaphoric artifacts of dreaming. Those half-human/half-animal dream figures seem to have their own agendas – as such they could be seen as expressions of our connectivity to our present ecological community.

Returning to the shamanic Big Dreams of the Elgoni, perhaps these intense experiences with “Other” reveal communication with the larger-than-human community through our personal mythic and metaphoric artifacts of dreaming. Those half-human/half-animal dream figures seem to have their own agendas – as such they could be seen as expressions of our connectivity to our present ecological community.

It’s no wonder Westerners describe horrific dream visions as well as benign, given our disconnect from the natural world and our techno-industrial assault on the living fabric of life itself.

Even without assigning “inter-species communication” or “Gaia consciousness” it seems plain that we are resistant to ecological information (and other collective levels of suffering) that comes through our dreams.

That’s definitely one of my strong biases – that ecopsychology (the study of our minds in relation to our environment) has the most inclusive way of looking at our behaviors, our emotions, and our visionary states. From here, we can frame Big Dreams as evidence for a “collective unconscious” that is not rooted in the distant past (or phlyogenic memory) but instead that bubbles up from the present moment, from our present relationship to the Others in our lives.

Ultimately, I wonder: does the world dream through us” And even if this is only a metaphor for our personal and communal journeys through life, how can we learn to listen?

Great post! I can’t wait until sanity returns and we don’t have to throw reductionist perspectives so many bones.

thanks Feral K. the reductionists have an important piece of the puzzle; the problem of course is that they think they own the whole pie.

I had no idea abstract geometric dreams were common! I used to have those when I was a kid, and they were very distressing, like an evil unseen presence, so I can relate to that shamanic ressonance that you talked about.

I only knew one person that recalled having the same sort of dreams, although for her they weren’t distressing at all.

I think sexual urges are the root cause of all human desires and dreams. combining with other secondary urges our desires are formed and the dreams as well which are the repressed desires of recent orlong past. plz let me know something in this direction.

Hi Samarjit,

that view is a clear description of Freudian metaphysics to be sure. I believe this layer of dream content and psychodynamics is part of dreaming. But obviously, as stated in this essay, I think there’s more to it than that. Freud gets the personal dimensions of dreams, and Jung focused on the transpersonal. both views are a piece of the pie.

Those interested in the dynamics and structure of dreams are invited to join my Carl Jung Depth Psychology Facebook Group: https://www.facebook.com/groups/56536297291/

Thank you

Those who have an interest in this topic will find plenty of dreams that exemplify this theme on my website http://www.openfoot.net where I have attempted to unfold the development and progression of “big dreams” across a lifetime. For better or worse my ramblings through internal landscapes are laid bare to the world. As a young man I didn’t know what had hit me. I hope that in the telling and valuing of dreams we might collectively reach a place of greater understanding.

Hello, openfoot, and Ryan, and all – I, too, have been “hit” by the same disease, it seems – ever since I was four (although in his 1999 book, David Foulkes, concludes, from his studies with children, that children before ages of seven or eight not dream). Now in my fifties, and for the past six years I have been working at a book on the why, what, and the when of such dreams – my argumentation is that dreams are windows into the big processes of life, like the evolution of consciousness; they show evolutionary, self-organizing patterns observable too in the complexity-chaos type of behavior of a whole diversity of systems that make reality.