Recently I have been inspired by the work of writer Matt Cardin—who you should be reading if you’re interested in creativity, horror and the divine. Matt also has lifted up the importance of personal journals in tracking the evolution of a writer’s life, as a snapshot of how our creative minds evolve over time, and sometimes, how we keep circling back to a few core ideas all our lives.

As it turns out, I already make a practice of re-reading my old journals from time to time. I’ve been keeping diaries since I was 13, so there’s a lot of material to work with here. The reading is always interesting because I come face to face with my-self, my foibles, and I usually get a real good belly laugh out of it too (because I generally make the same mistakes over and over).

All in all, when rereading an old journal, I delight in remembering what otherwise would have long been forgotten.

Because we forget so. very. much. It is shocking.

So this week, I found a delightful passage about my dreams from 1999. Or “the nineteen hundreds” as my son likes to say.

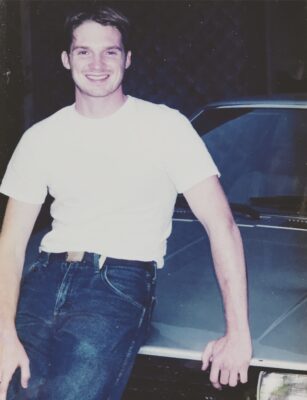

This was a pivotal time in my young adulthood, a time when I was a semi-nomadic field archaeologist, roaming the country with shovel and screen. Between stints at my old basement bedroom in my parent’s home, I lived out of my 1982 Toyota Corolla.

Like most folks, I didn’t have a cellphone yet, and wow I am glad social media wasn’t around documenting my movements.

So I wrote the following entry on May 28, 1999. I was backpacking alone in Uhwarrie National Forest, camped out along a small stream for the weekend before I was due to report back to archaeological data recovery (excavation) in Cumberland County, North Carolina, working for Wake Forest University.

Midmorning in the forest—it is cool and peaceful with the sun splicing in between the trunks. I’ve got a fire going again—this time it really is small and ceremonial! Last night became a blaze of light by which to set up my tent and read. Slowly reading Suttree [by Cormac McCarthy]. It’s excellent, hilarious dialogue, deep sense of place of 1950s Knoxville.

I woke up with my head full of dreams, and had the luxury of just lying there for 20 minutes remembering them, one by one, literally pulling the string out of the wall as Sterling Watson likes to say [my creative writing professor from Eckerd College].

I dreamed last night that I was in a small Unitarian church—like Athens [GA]—and was about to give a speech as Kurt Vonnegut. Only mom and dad knew my real identity. I rehearsed, somewhat frantically at this sudden duty, and my talk was going to be from an old man, bitter with age and handicapped, explaining how he once was young, too. I was going to give a talk from a microphone, in a curtained off area in front of the congregation. Just as I picked up the microphone, another woman starts talking—so we talked off, the dream fumbled.

I don’t try to interpret most of my dreams these days, mostly because I think it’s bunk. Emotional intensities are real, but a flower equating love eternal is bullshit new-ageism.

More important than what the dream “really” was saying (which is impossible to know) is how we interpret it once we’re awake. The connections I draw now say more about my life than perhaps what the dream was. I know this way of thinking is frighteningly close to postmodern literary analysis—in which you bring your own issues to the text—but it’s practical.

A dream might as well as be a text, so unknown is its author.

What strikes me is that, all these years later, the themes from this dream continued to develop throughout my life: questions of faith, of identity as writer and scholar, of finding my voice. And there’s plenty more I can say about this dream today that would make my 25 year old self blush, including some quasi new age bunk about the constant emanating presence of soul that guides our journey through life.

I’m also reminded of Kenneth Koch’s classic poem:

“To my Twenties: …I’m still very impressed by you. Whither,

Midst falling decades, have you gone? Oh in what lucky fellow,

Unsure of himself, upset, and unemployable

For the moment in any case, do you live now?”

Finally, I’m noticing how, all these years later, I am still focused on how to keep dreamwork practical and evidence-based. How the process is as important as the results. How the dream is not “saying” anything like a message to be decoded, but rather is a lived experience. And how our projection onto our dreams (and other people’s dreams) may be just as revealing about our worldviews and paradigms of reality than the dream itself.

Do you keep a journal? My unsolicited advice: start today. You’ll quickly see what a brilliant tool journaling is for self-discovery and, later, remembrance.

Hi Ryan,

In my elementary school we were required to keep daily journals, which I disliked at the time. Part of the reason was that I was the kind of student who would always choose to do an oral report over a paper when given the choice. I didn’t find my true personal writing style until college, and I remember being in high school when the SATs added the written essay portion to the exam.

I find dream journaling easier to do personally, because the dream itself is a prompt, and there aren’t strict rules about writing in complete grammatically correct sentences or minimum page limits like in academia.

My elementary school self would be very suprised that as an older teen and adult I write by choice.

Thanks for sharing your process — I can relate to that! My elementary school self would be flabbergasted that I became a public speaker. I used to blush every time I got in front of the class!

Dream journaling is a great way to get into the process of journaling in general too — because as you say, there’s really no rules. And you can just report back what happened, and how you felt about it. It’s a process that by itself unfreezes our minds from the inner critic.