This is a guest post by historian A.L. Castonguay. Whenever we see an image of someone who is “sleep deprived” what do we usually see? A parent with children? An overweight or obese person –or one who’s underweight? Someone living in a rural district? Is it a person of color? Chances are, we see none of that. Instead, we may actually see an image of a white man rushing from one meeting to another, or a white woman in a business suit trying to shake off fatigue in a meeting. What gives?

Because of these images, sleeplessness is presumed to be a result of this busy, demanding, upper-middle class lifestyle; if you simply adjusted this, you wouldn’t need that extra coffee.

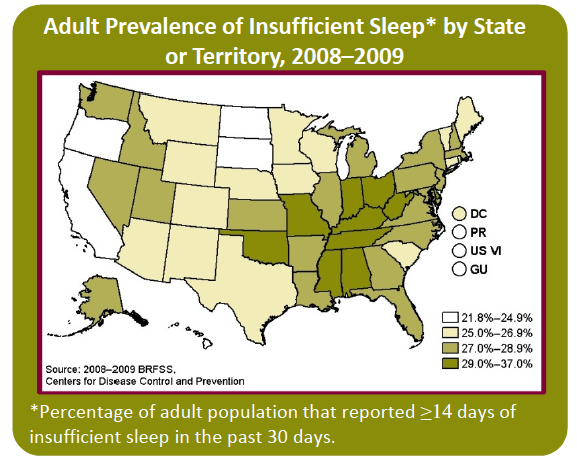

Yet data released by the Center for Disease Control (CDC) on sleeplessness in the United States does not line up with these images.

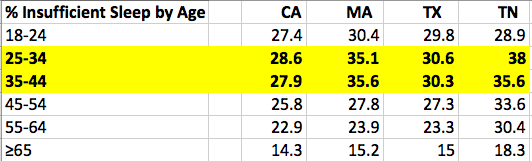

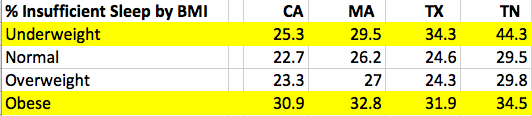

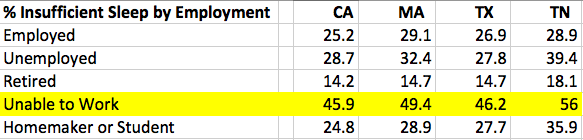

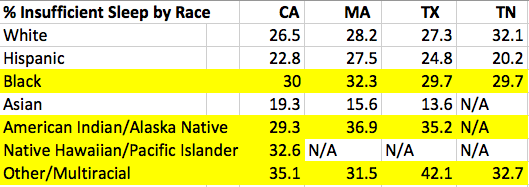

Instead, what comes out is that those who report higher instances of sleeplessness, defined as insufficient sleep (less than 7 hours per night) on more than 14 days within the past 30, are predominantly people of color–in particular Black/ African Americans, Native Americans & Hawaiians, and those identifying as other or multiracial)–between the ages of 25 – 44, unable to work, and obese.

For the sake of this post, I’ll be comparing data collected in California, Massachusetts, Texas, and Tennessee, four states with different populations and reported levels of sleeplessness, but ones that still show these trends in spite of their differences.

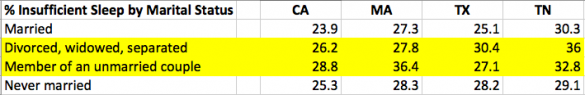

Additional increases in sleeplessness was also reported in those with children, those in relationships but not married, and those who are unemployed. Those who reported sleeping the best were those 45 and older, which is interesting since sleep quality–as defined by percent of restorative sleep vs disrupted sleep and time spent awake–markedly declines as we age.

So what should we make of this? What is the best way (if any) to look at such information?

Should we come to the assumption that our previous ideas about who is sleepless are false –and might be, in fact, marginalizing those who are actually reporting greater instances of sleeplessness by not depicting them in health campaigns or advertising?

[pullquote]What about the social and racial aspect?[/pullquote] Should we be looking at sleeplessness in terms of overall health, as many sleep experts argue, and explore correlations between obesity?

Should we look at it from an economic viewpoint, and acknowledge that being unemployed, as opposed to retired, a student, or a home maker, may in fact have a higher toll on individuals? (a great question in a time of lingering unemployment and forced joblessness).

What about the social and racial aspect? Should we make anything of the fact that historically marginalized minority groups are reporting lower sleep quality — and that they have, on the whole, reported an overall lower quality of life than whites or East Asians?

Perhaps what needs to be done first is a wholesale reminder of what exactly it means to report insufficient sleep.

Sleep is a public health issue

On the surface, it appears that we as a society are coming around to the idea that insufficient sleep is a health issue. There have been numerous papers, studies, and news articles on the link between poor sleep and increased rates of diabetes, weight gain, cardiac issues, and time it takes to recover from a cold or infection.

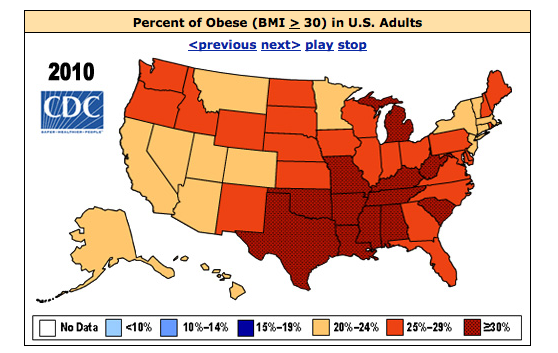

What is new is that there appear to be correlations between obesity and income and education levels as well. Those who are obese tend to have completed less education than those who are normal weight, and those with less education typically earn much less than their more educated peers. In regions of the US where only high school or some secondary education is the norm, we can assume that the obesity level will be higher than in those regions where secondary education is the majority.

Again, given the connection between poor sleep and obesity, we can therefore hypothesize that areas where obesity is greater, instances of sleeplessness will also increase.

However, despite this information, lack of sleep is still depicted as a product of a busy, hectic life — a life increasingly associated with the upper middle class.

Yet again, the CDC data tells a different story, illustrating a strong correlation between poor sleep and the chronically out of work across all 50 states.

It’s worth noting that those with disabilities report higher than average instances of unemployment than those without; in 2011, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that 17.8% of those with disabilities were employed compared to 63.6% of those without.

It’s also worth noting that having a job — in particular, one that is engaging– has been linked to a higher reported quality of life, which, in light of this data, may translate into better quality sleep.

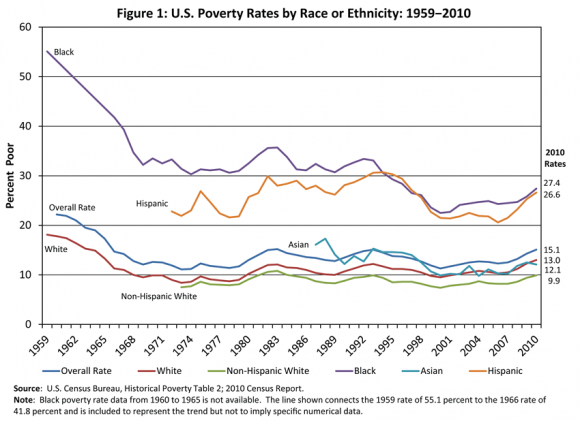

This same data also suggests a strong correlation between historically marginalized minorities, such as Blacks/ African-Americans and Native Americans, and poor sleep quality, which may be related to a historically lower quality of life brought about by said marginalization. Poverty has long been identified as a significant factor in one’s overall health and well-being; it has also been identified as disproportionately affecting large segments of the US population.

Source: http://www.irp.wisc.edu/faqs/faq3.htm

And again, with the strong correlation between sufficient sleep and wellness, it can be argued that those who do report insufficient sleep may have other issues to contend with that are not as obvious on the surface.

And what exactly do we do for those are in a serious relationship but who, for one reason or another, are not married? Is the lack of a legally recognized partnership –which could yield additional financial benefits— contributing to poorer sleep quality? Or is it a lack of economic activity, which is appearing to correlate strongly to those of a lower economic class, preventing marriages that, a generation or two ago, would have taken place – and brought a sense of stability along with it?

This chicken and egg quandary does make it hard to address the issue of sleeplessness at hand. In order to combat the fact that a 1/3rd of the US is statistically sleep deprived, do we roll out public service announcements stressing the importance of a good night’s sleep?

Or do we focus instead on related issues, such as the importance of work in maintaining overall health, or the ways in which certain ethnic and socioeconomic groups in the same country appear to have vastly different lives?

What’s next?

It will be interesting to see how the CDC decides to make use of the information it has collected. Optimistically, one hopes that such an organization would continue to highlight the importance of a good night’s sleep for everyone–and make lifestyle suggestions, that can be applicable regardless of one’s particular background, such as keeping a set sleep schedule–but also take the steps needed to ensure that it is made a priority across all reported groups. This might mean that different approaches to the problem of sleeplessness are needed, but with the known positive benefits of a life of good sleep, it’s arguably well worth the effort.

And along the way, who knows? Perhaps our own perceptions of those who miss out on sleep will change as well. It might finally become the communal health issue, instead of a lifestyle choice, that it is.

About the Author

A.L. Castonguay is a historian and writer who’s always looking at the ways in which seemingly unrelated things are connected in modern society. She currently explores this and more over at notjustmyblog.com. From 2010-2012, she was also the editor of Zeology and the Zeo Knowledge Center, two sites devoted to the mysteries and science of sleep.

First image: CC Morning coffee by Andre Bulber

Ryan, thank you for this timely research. It is very pertinent to my client populations.

Abundant blessings,

Susan

Hi Susan,

I’m glad you not only liked the post, but you found it to be incredibly useful as well. Here’s hoping the CDC keeps exploring this question further, so that we can make better decisions going forward.

Best,

a.l. castonguay

Thank you A.L. for challenging popular notions (and images) of who’s losing the most sleep in our country and why. The statistics and graphs are great – and more elucidating than any I’ve seen. I wish we had a good way to measure a sense of safety and security – two things that we need to be able to sleep well, and often lacking among the marginalized. I work with trauma survivors, and most of them sleep very little, for obvious reasons. Thanks again A.L. – and Ryan for offering this space.

Hi Kat,

Yes, feeling safe and sleep are certainly related, especially as feelings of insecurity deepen or grow over time. Like many things, it is tricky to qualify and quantify – but I’m glad that there are people such as yourself who are working to help others tackle this problem. The more insight we have –and the more we share said insight–the better for all involved.

I can personally verify that over the course of several years lack of sufficient sleep will slowly destroy your body and your mind. I have numerous health problems, and it all started with insomnia. I developed insomnia as a result of a very stressful situation at work, but I simply lived with it for years instead of taking any action. Our culture not only devalues sleep, it actually looks upon it as a vice. People who get plenty of sleep are seen as lazy and wasteful. Maybe this is why I didn’t take the problem seriously until I ended up in the hospital. This is a problem of the entire American culture, not just among select groups.

Hi Morgan,

Thanks for sharing your story. Sleep in our society is such a complex issue, with many different parts and scenarios, that it is hard, if not impossible, to wrap it all up in a nice little package. I do agree with you that there is a sense that “sleep is for the weak or lazy”, in much the same way that poverty and joblessness are “signs of laziness”. However, as I said to Kat, the more we hear of different sleep stories, statistics, and experiences, the more we can realize that sleep is not simple –and shouldn’t be treated or dismissed as such.

But doesn’t it all basically lead back to stress? I admit that my perspective maybe isn’t very scientific, but I think scientists can sometimes complicate things unnecessarily. Stress and, as another poster pointed out, a feeling of not being “safe” anymore have a catastrophic effect on sleep. I’ve noticed as I’ve gotten older (I’m 44) that my mental tolerance for stressors has decreased markedly. Of course, this might also be a symptom of inadequate sleep. You’re probably right that there are many factors involved, and thinking about them is just going to make it that much more difficult for me to fall asleep tonight.

I also wonder for those finishing college and unemployed with a rather hefty student loan bill will have an effect on sleep/health. Sounds rather rheotorical to me.

Hey Ryan, I really appreciate your post and research you’ve shared here. Sleep really is a #1 priority when it comes to health, and our happiness (along with proper diet of course). It’s just such a shame our culture takes it for granted.

By the way, LOVE your website!